Since early 2024, the Department of Urban Planning and Design at the Budapest University of Technology and Economics (BME), together with the Hungarian Contemporary Architecture Centre (KÉK) and the Józsefváros Urban Development and Rehabilitation Company (Rév8), has been collaborating as the Hungarian partners of the international consortium of the DUT, InclusiveCity project. In the 15-minute City pathway context of the European Driving Urban Transition (DUT) program, aiming to rethink the current mobility system and urban layout, but also restructuring daily activities to create cities that are more climate-neutral, livable, and inclusive1, this project focuses on the critical rethinking of the practice of placemaking, to strengthen the role of inclusivity in public spaces. The project includes five pilot Urban Living Labs (ULLs) set up in Budapest, Oslo, Rome, Rotterdam, and Vienna. The following article presents a report on the educational experiments and on-site activities initiated by BME contributing to the project, which took place during May and June 2025 at the Budapest ULL: Népszínház street.

Social and physical context

The target intervention area (ULL) of the Hungarian partnership is located in the 8th district, also called Józsefváros. In Budapest, there is a special two-level municipal system where the central government mainly shapes urban development policies. In contrast, the districts have much larger responsibilities in urban affairs: among others, they manage zoning plans and urban renewal initiatives, launch community projects, and implement public space renewal projects. Since the early 2000s, the 8th district has initiated several such projects with EU development funds, including comprehensive social renewal programs focusing on crime prevention, housing renewal and public space renewal with pragmatic and sometimes explanatory tools, resulting in a slow but steady urban requalification of the district.

Being on the border of three quarters2 inside the district – Csarnoknegyed, Magdolnanegyed and Népszínháznegyed – Népszínház street can be regarded as a central alley of one of the ethnically most diverse3 and economically most disadvantaged4 districts of Budapest.

Népszínház street connects Blaha Lujza square at the Great Boulevard with Teleki square next to the former Józsefváros railway station. These two endpoints played significant roles in the history of the street: the name of the street is connected to the former, while the latter contributed to the development of urban life in the street. The building of Népszínház (People’s Theatre) stood in the area of Blaha Lujza Square until its demolition in the 1960s. Józsefváros railway station used to be the entrance of Budapest from the end of the nineteenth century for many seeking jobs and better futures in the city. Due to the close proximity of the railway station and developing industrial areas, the street became an attractive location for entrepreneurs to open small-scale shops in an era of economic and demographic boom.

However, the railway station gradually lost its importance after the opening of Keleti railway station nearby until its permanent closure at the beginning of the 2000s. The generous width of the street, the once representative facades of several buildings and the few remaining entrepreneurships resemble the prosperous past. Népszínház street is traditionally a hub of several minority groups (in the early twentieth century they were mainly Germans, Slovakians, Roma people and Jewish communities). Nowadays, the street is an attractive location for many immigrant communities from the Middle East, Far East and Africa, aiming at starting businesses due to the central location and the relatively cheap rental prices of the street. The historic physical and the multicultural social properties make Népszínház street an area full of tensions and potentials.

Here, the main target area of the project is located in and around the municipality-owned premises of a former post office, which lost its function a few years ago and is looking for new possibilities to upgrade the street.

Népszínház Everydays: towards the understanding of the life of a street

On May 24-25, the former post office at Népszínház Street 42-44. was transformed into a vibrant exhibition space by international architecture students. The event was part of the Budapest100 architecture and cultural festival, showcasing unknown, but valuable historic buildings and tenement houses in Budapest. As part of the InclusiveCity project in the previous semester, several student projects focused on exploring everyday life along Népszínház Street. The exhibition presented the outcomes of these urban research practices through thematic installations, based on experimental methods developed during the courses.

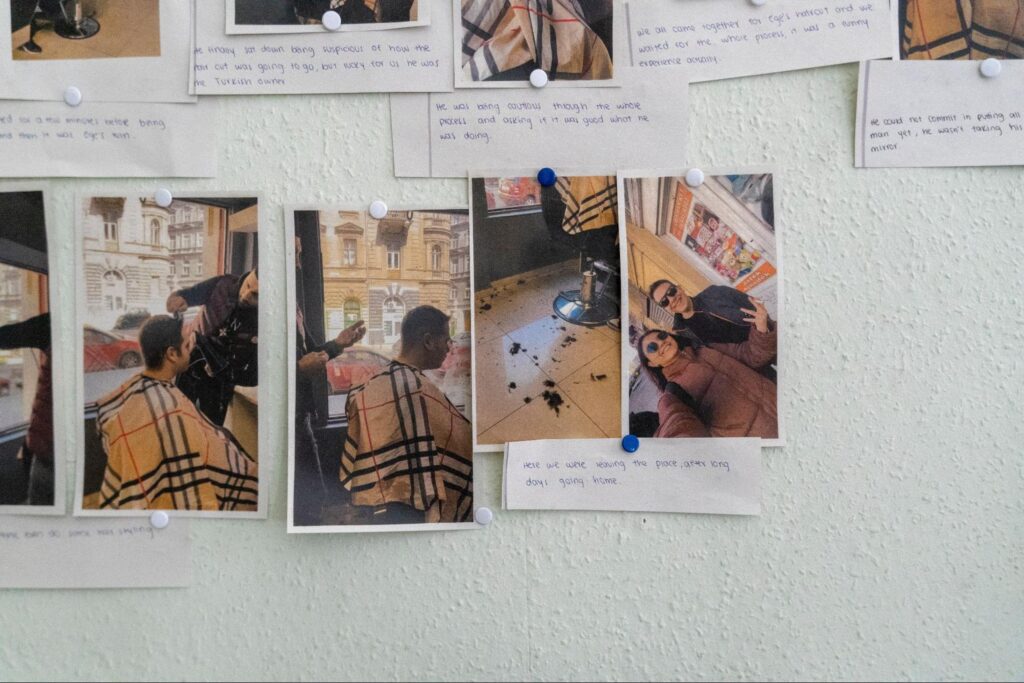

The central installation of the exhibition was entitled WHAT CAN THE STREET GIVE YOU? – Discovering Products and Services of Népszínház Street. One side of the main space was covered with photos and textual notes from students during their interviews and visits to 18 local shops and services at Népszínház street. Students were not only passive observers and interviewers but they also took the challenge of trying out the services offered by local entrepreneurships: among others they made their hair cut in a Turkish barber shop; made their nails painted in a Chinese manicure saloon; made their laundry washed in an Indian laundry shop, and received an insight into their future through Tarot cards by a Hungarian fortune teller. Through these encounters, students had the opportunity to gain rich, first-hand insights from street life. Video documentation of the explorations and interviews:

Micro-documentaries on Everyday Streetlife was another installation that presented a selection of short videos students captured about life details on the pavements of Népszínház street. Seven reused smartphones played observations simultaneously about topics such as body language of people, daily rhythms of walking, acts of entering and leaving the street, how people cross the street, how people rest in the street, and how people work on the street. Such an exercise is aimed at making students focus on and structure their experience of everyday, mostly overlooked phenomena that take place in the built environment, for the design of which they will be responsible in their professional career. Videos presented in the exhibition can be viewed here: kiállítás_street_videók

Book of Dérives is a publication first introduced at the exhibition as well. The volume is a collection of 20 one-hour-long individual voyages of architecture students, for whom this occasion was the first encounter with the street itself. Students had no obligation of what to do during their stay; they could simply let themselves be led by the street. They documented their experience in illustrated diaries that are presented in the book. The digital version of the volume can be found here: BOOK OF DERIVES.pdf

In addition to the projects inside, several activities took place outside of the Post Office transforming the street into a crowded meeting spot: concerts of local folk musicians, gastronomic performances of students, guided urban walks, onsite surveys coordinated by the team of Rév8 among others kept the street lively in an unexpected way for whole weekend providing a platform for a heterogenous audience from the residents of the nearby temporary shelter to the local and international intellectual visitors of the Budapest100 program to share space and time together.

Tactical interventions as tools to generate Inclusion: placemaking camp in Népszínház street

Following the pop-up exhibition at the end of May, an urban camp was organised from 10-13 June with the participation of architecture students from BME. The camp base was again located at the former post office at Népszínház Street. Each day, students designed simple, action-based public interventions, which were tested in the afternoons both on the street and in a temporarily reclaimed parking space in front of the post office. The shared goal of the interventions was to make passers-by stop for a while, engage them, and discover some unexpected alternatives for how the street can be used. Group discussions concluded that in order to reach this aim, we should use ‘play’ as a main tool. The challenge for students was to find ways to invite city dwellers to step out of their everyday rush and choose moments of playful activity instead.

On the first afternoon, a public vote was organised, when students’ concepts about the possible reuse of the post office and about development alternatives for the whole street were displayed: people could share their opinion about the ideas and vote for the ones they preferred.

On the second day, water was used as the primary material, an element hardly present anywhere on the street: students turned the parking space into a temporary pool and funfair. The sudden appearance of a water surface in the asphalt desert of the street triggered several spontaneous encounters: people walked into the pool playing together, started spontaneous fishing or just stood at the side watching the gurgle of water made with a simple garden sprinkler. The presence of water created an atmosphere: it transformed the parking space on the street into a spot to stay, talk and play for a while.

Students developed some further instruments for play: for one day, they turned the parking space into an adventure park, where participants had to rely on their physical abilities to make their way through a miniature obstacle course resembling an oversized spider web.

In addition to the daily play events, members of the Rév8 team were also present, conducting interviews with participating people. To serve the physical environment of this activity, students extended the iconic cargo bike of Rév8 by building a very simple foldable desk that can be easily attached to the platform of the bike, creating a counter ideal for the participatory mapping activities of the Rév8 team.

It is relevant to note that this camp focused on processes rather than products. Though students spent the day preparing for the afternoon’s upcoming event, the actual value did not lie in the outcome but in the shared process: group discussions, common preparations and other activities on the streetside and at the parking lot. These activities embodied a temporary occupation of public space, where the most critical aspect was that through this presence, we created vital points of connection with residents. In effect, the group transformed the street in front of the post office into a public living room, open for anyone to join. During the week, local NGOs and organisations like Internép, Auróra or Lehetőségek Tere visited the students, and the group also had some walking tours to socially engaged local venues like Tolnai kert, Dankó udvar or the recently opened Szeszgyár köz a public square equipped with instruments aimed at motivating people to play.

As the highlight of the camp, Rév8 invited the students to participate in the street festival celebrating the renewal of Szeszgyár köz. Alongside children’s activities, the students exported and reinstalled the interventions made during the camp, adapted to the environment of Szeszgyár köz. They also designed a unique board game: they built an abstract 3d map of the neighbourhood onto a piece of cardboard, and people had the chance to reproduce their daily walkpaths by rolling a tiny glass ball through the slight lifting of the board’s corners.

The pool was remade as well, which acted as an unexpected object of amazement in Népszínház street, where mainly curiosity made people come closer. However, at the festival of Szeszgyár köz, people had no doubts about how to relate to this water surface: it turned into a children’s pool immediately.

Conclusion

During the camp, it was a conscious decision to make interventions that were both highly related to the actual site but mobile enough to be rebuildable at different locations. The two locations – the pavement extended with a carpark area in front of the post office in Népszínház street, and Szeszgyár köz that is a public square with a playground – showed that different physical and organizational situations induced highly different perceptions and activities of the same object: at Népszínház street the projects intervened into the flow of everyday life when people mainly focus on their daily routines. We wanted to make people stop for a while and invite them to start thinking together about the presence and future of the street. Thus, we needed actions that created surprise and unexpectedness, which are reactions bearing the capacity to suspend accustomed behaviours temporarily. The event at Szeszgyár köz was a municipality-initiated public festival advertised among locals before the event. So people could prepare for the event; thus, surprise was a less relevant factor in this case. This was a common feature of the Budapest100 program in May as well. During these events, it was unnecessary to make people stop since they arrived on purpose; the challenge was creating a platform where people from different backgrounds could meet and acquire a common experience. The installation of a water surface proved effective in both situations as it was able to subvert people’s attention, and it managed to provide community space as well.

The interventions as objects were low-cost, simple, and less relevant than the activities they triggered, not just during but before and after their operation. In case of the Szeszgyár köz festival, for instance, students found out that there is no adequate water supply at the site to fill the pool, so they asked for help from local entrepreneurs and received unexpected support from the community of Gólya, who made a cargo bike available for the students to carry several buckets of water from their place. After the event’s closure in the evening, children who used the pool helped dismantle it, and they irrigated the plants of the square with the remaining water. As a result, the project is not regarded as the celebration of a special object but as a series of activities where many people – from local children and their parents to university students and members of NGOs – cooperated for the same purpose: to make an event happen that they regard as a meaningful and enjoyable contribution to the place where they live.

Participants:

Népszínház Everydays exhibition:

- Tutors: Gergely Hory , Bálint Kádár, Valentina Fesenko

- Students: Hubert Jakub Barnik, Deniz Bayar, Helga Berner, Celia Gil Torroba, Elodie Marie Murielle Grandemange, Leticia Monika Mejías Wandycz, Eduardo Antonio Ollervides, Marta Regidor Santana. Ana Sabater Salgado, Martin Varema, Stephanie Alain, Domenica Chavez Arcos, Yue Cui, Joao Victor De Leliz Somensato, Akzhan Fatykhani, Sandy Mofreh Lemby Hana, Ivana Ilic, Ege Ozan Simsek, Jinrui Tang, Wenhai Tao, Marion Barde, Tímea Fazakas, Eszter Laura Borbély, Nuriya Serikbayeva, Nguyen Phuoc Phuong Uygen, Malika Sagynayeva, Olivia Basily, Alaa Hamoda, Salma Haourari, Vojtěch Košák, Karol Golik, Jules Schmitt, Julia Ruano, Juan Garcia, Negro Sanz Rocío, Yakit Baris, Baddour Karim, Zhang Xinran, Vivien Nwanze Nneka, Isidora Markovic, Borislava Cucic, Tsogbaatar Margadgua, Sodbayar Nyamdorj, Baatar Bilguuntuguldur, Isadora Marquez Rocha Machado, Imane Tamazzaurt, Luisa Valerie Hartl, Yasmine El Bada, Ana Pérez Gantes, Melisa Tugba Gündüz, Paula Garau Ruiz De Peralta, Unenkhuu Ganbold, Marta D Innocenti, Victor Daniel Jacques Colliot, Anastasia Kleitsiotou, Sohye Yeom, Inasse Aissatin, Eliott Rondeau, Estelle Elise Daguzan, Achraf Azarou, Sara Navarro Cozcolluela, Safae Serghini, Emma Rosa Joséphine Michel

Placemaking camp:

- Tutors: Gergely Hory, Imre Varga, Árpád Szabó, Márton Révai

- Students: Veronika Zita Bukovszky, Dániel Dézsi, Dorina Hanyecz, Eszter Kis, Hajnal Lukács, Szonja Márhoffer, Janka Mátis, Márk Neuhauser, Fanni Tóth, Vince Vigyikán, Zsófi Jedlica, Janka Regölyi, Áron Hegedűs, István Ferdinandy, Zóra Eszter Vida, Csongor Csepregi

Contributors from RÉV8: Lilla Gerencsér, Rebeka Horváth, Viktória Kocsis, Lonci Tóbiás

Contributors from KÉK: Barbara Bozsik, Kata Csala, Dóra Kondora

The project 2024-1.2.1-HE_PARTNERSHIP-2024-00009 is co-funded by the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme, with support from the Ministry of Culture and Innovation’s National Research Development and Innovation Fund, in the framework of the Driving Urban Transitions (DUT) partnership.

- https://dutpartnership.eu/the-dut-partnership/the-15-minute-city-transition-pathway-15mc/ ↩︎

- In order to strengthen the local identity of neighbourhoods the district introduced 11 “official” quarters in the district with legally defined borders. ↩︎

- Accoding to the population census of 2022 34% of the district’s population identified as member of an ethnic nationality other than Hungarian ↩︎

- The amount of yearly legal income per person was the lowest among Budapest’s districts according to the data of the National Tax and Customs Administration from 2020. Source: https://www.ksh.hu/docs/hun/xftp/idoszaki/pdf/korkep_budapestrol_2020.pdf ↩︎