Set in a near-future dystopian England, the opening scene for V for Vendetta begins with a public-service announcement: “People of London, be advised — that Braxton and Streathon are quarantine zones as of today. It is suggested that these areas be avoided for reasons of health and safety”. A wary Natalie Portman walks through the gloomy streets of London, and the local loudspeakers blare: “A yellow-coded curfew is now in effect, any unauthorized personnel is subject to arrest. This is for your protection”1.

Dystopic. Surveillance capitalism. A destruction of democracy. These are some of the critiques thrown against ‘Smart Cities’—technology-dense urban areas which utilize sensors and other electronic solutions to collect data and improve operating efficiency. Given the above scene and similar representations of technology in the media, the public’s skepticism to mechanizing cities is easy to empathize with. In urban spaces, the image of technology evokes feelings of top-down control; of the artificial; of the non-human juxtaposed against the human. At first glance, the ethos of a technological city appears to be completely opposed to the aims of placemaking. The rigidity and dominance of technology appears contrary to the bottom-up, community-driven initiatives; principles of “lighter, quicker, cheaper” so intrinsic to the practice. So, are technological initiatives doomed to fail in light of human-centric approaches? Not always.

Broadly defined as a collaborative practice for revitalizing public space, placemaking aims to create a sense of place for communities, strengthening the connection between people and the places they share. Placemaking aims to break down some of the rigid, institutionalized planning practices that have taken hold in the 20th century; instead emphasizing context-specific approaches that highlight a local community’s assets—the physical, cultural, and social identities that define a place2.

When described in this manner, it may seem like a natural comparison to pit the rapidly revolutionizing technologies against placemaking. However, increasing attention to the field of responsible digitization begins to show how the two may be more alike than different. Much of the critique of “smart cities” appears to stem from concerns that remove people from processes—whether it be in automation, autonomy, or transparency. Placemaking would argue that these concerns may be addressed through practices that put people and places at the center. As such, what if the processes of humanizing technologies and humanizing cities were much more alike than previously thought? This blog examines the ways in which placemaking can be used to ‘humanize technology’, helping to create healthy and inclusive cities in the process.

Launched in 2021, The Responsible Sensing Lab is a collaboration between the City of Amsterdam and the AMS institute created to explore how societal values can be embedded into the design of urban sensing systems3. Looking to Amsterdam’s Digital City Agenda and the TADA ‘responsible city’ manifesto, where some of the aims include: “inclusive”, at the “human scale”, “open and transparent” and “from everyone – for everyone”, these principles appear to closely mirror placemaking aim’s of inclusive, participatory, and community-driven development. Aligning these values reveals a trajectory where technology, especially responsible technology, moves towards becoming increasingly people-centered.

Drawing upon projects from the Responsible Sensing Lab and similar initiatives, this article showcases instances where the processes of humanizing technology closely mirror the processes of humanizing cities: what happens when humans and technology work together? When humans are able to intervene in automated decision-making processes? And when technology, too, can become “lighter, cheaper, faster”?

The Mobile Robot Bin: Humans and Technology Working Intandem

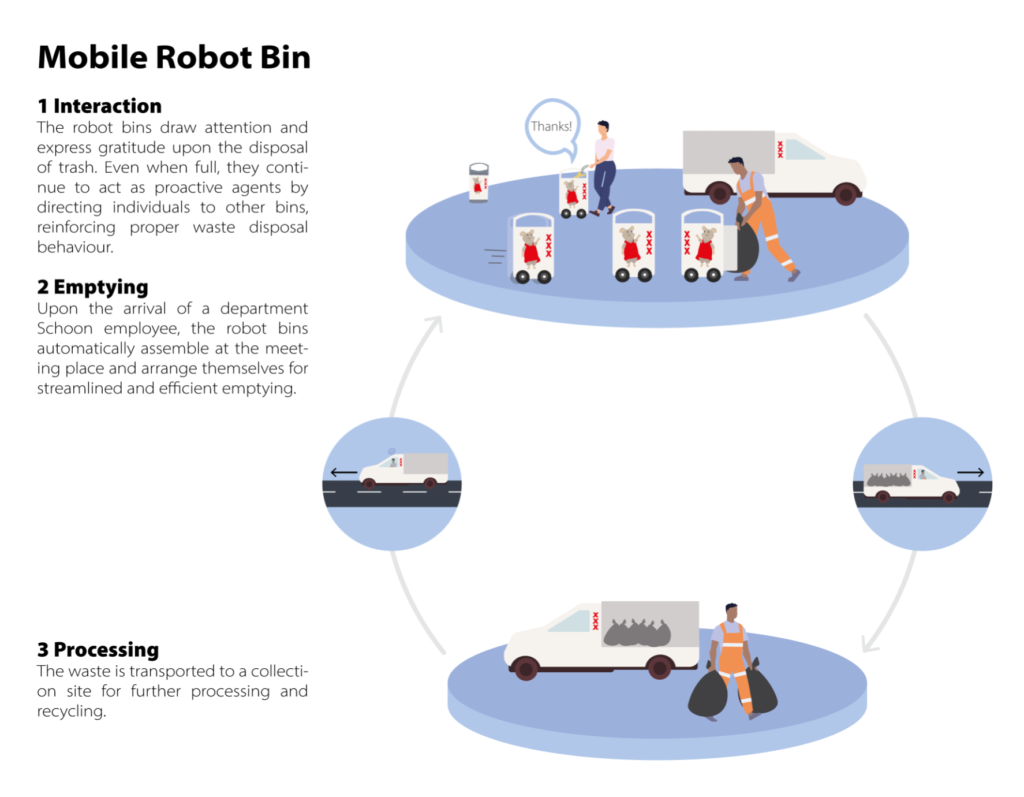

In one of the projects from the Responsible Sensing Lab, design engineering student Claire Schumann explores how humans and robots can work in tandem in order to alleviate the city’s waste management problems. In her master thesis, Schumann finds that the presence of cleaning robots may lead to a reduced sense of personal responsibility for individuals’ waste, potentially exacerbating littering behavior4. To address this, the designer conceptualized the Mobile Robot Bin, which aims to actively involve community members in the process of waste disposal, rather than simply cleaning up after them5.

With human-like features, the Mobile Robot Bin is an autonomous robot bin that engages users by rewarding proper littering behavior. The robot moves around within a designated area, performing actions such as expressing gratitude when trash is properly disposed of. When it came to the design of the robot, Schumann also wanted to actively engage community members, aiming to present the community with a number of design options and allowing them to choose. She says this would both foster “a sense of ownership among the residents” and prepare them “for the arrival of the robots”. Schumann’s current design concept draws upon Karina Schappman’s artwork, an Amsterdam artist known for her work on ‘het Muizenhuis’ (the Mouse House)6.

Schumann’s project illuminates an important lesson in the project of humanizing technology: the importance of involving humans both in the design process and final output. In Schumann’s conception, humans and technology must work alongside one another. Without this premise, technology may tend towards its domineering dystopian image. The interactions built into Schumann’s robot also embody essential tenets in placemaking: her focus on human-robot interaction and engaging the local community instigate an intervention that is context-specific, collaborative, and community-driven. The location-constrained working area of the robots make it another contributor to a community’s sense of ‘place’: from its design to its expression of gratitude, the anthropomorphic features of the robot make it appear friendly and sociable; aiding in the creation of place and undermining associations of autonomous technology with being invasive or foreign. Similar approaches are being employed to other autonomous urban interventions, from MIT’s Roboats to the UNSense’s Scan Cars. In order to circumvent dystopian futures, a human-centered approach is crucial; an interplay between humans and technology avoids top-down approaches that employ technology as the end-all be-all solution.

“Lighter, quicker, cheaper”: Inexpensive, Deployable, and Adaptable Technologies

At a brief glance, the image of technology may appear contradictory to placemaking’s mantra of “lighter, quicker, cheaper” interventions. After all, most technological interventions are formal, costly, and take large amounts of time and resources to implement. However, an increasing number of projects demonstrate how new technological interventions could parallel their DIY, citizen-led sister; as new innovations have proven their ability to be ‘low cost’, ‘low-tech’, while also staying ‘data smart’.7

From helping report air pollution levels to putting informal housing communities on the map, the rise of citizen-science led initiatives have led to inexpensive, deployable, and adaptable technologies. Utilizing community members also means that the projects are inexpensive, deployable, and adaptable. Urban AirQ, an air-quality measuring pilot launched by Amsterdam Smart Citizens Lab in 2016, notes that measuring air pollution is highly difficult due to the level of precision required to detect small changes in concentration. Traditional air monitoring stations also have difficulty capturing local variations in air quality, and financial constraints can also limit the size and scope of current monitoring networks8. This makes citizen-led approaches an attractive alternative. Such projects often aid in addressing concerns about data collection and privacy, as community members are the ones collecting the data, while also stimulating awareness and public participation.

Another citizen-science initiative, the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team (HOT)’s open source data collection brings together thousands of volunteers to place ‘on the map’ areas that are vulnerable to disaster. The organization works through the platform OpenStreetMap, a free, community-driven, editable map of the world. The data that emerges through open-source mapping allows responders to reach those in need—addressing issues ranging from disaster and climate resilience to displacement, safe migration, public health, and gender equality9. Echoing the “lighter, quicker, cheaper” mantra, utilizing open source data collection makes the projects transparent, low-cost, multimodal, and efficient. Such platforms make possible the collaborations between technology and community, serving the aims of people-centric urban sensing systems.

Contestable AI: Enabling human intervention by design

With the introduction of Contestable AI, TU-Delft PhD student Kars Alfrink begins to unravel some of the debates that have surrounded the use of artificial intelligence—from concerns about AI undermining democracy to its effect on basic human rights10. However, ‘contestability’, Alfrink proposes, offers a way into addressing such concerns about harmful automated decision-making.11

Stemming from the premise that models are not infallible, contestability is defined as “humans challenging machine predictions”. Enabling human intervention, contestability provides opportunities for human controllers to intervene before ‘failed’ automated decisions—fallible, unaccountable, illegitimate, and unjust—decisions are applied. In addition to ensuring human control over automated systems, contestable AI gives voice to “decision subjects”, protecting human agency and increasing perceptions of fairness, especially for marginalized or disempowered communities. In this way, researchers have argued that contestability should be part of the entire AI system development process, launching the practice of “contestability by design”. 12

In launching the concept video for contestable camera cars, themes that emerged from participant responses—enabling civic participation, ensuring democratic embedding, and building capacity for responsibility—closely mirrored placemaking’s own aims of dynamic, participatory, and community-driven interventions. Although not new, the acceptance that automated systems are not immune to failure—hence room for human correction should be embedded into their design—is quite revolutionary. The idea works to counteract long-held paradigms of technological mechanizations as more accurate and intelligent than human cognition; hence deserving of more control. By allowing automated processes to be challenged, contestable AI yields control back to its users, helping navigate the paradigm of top-down control often associated with technology. Returning the mic back to traditionally marginalized communities also creates room for more participatory decision conditions in the tech domain, enhancing placemaking’s aims of inclusivity.

To circumvent the dystopian futures foreshadowed by sci-fi literature, it may be time to seriously consider and critically apply the processes of placemaking to tech-oriented Smart Cities. Technology mustn’t be limited to its associations with non-human, rigid authoritarian control. By intentionally placing the human as central to the process, we create opportunities for tech to be collaborative, dynamic, low-cost, and democratic.

In addition to addressing the human vs. non-human divide, reconciling these binaries also offers opportunities for targeting other divides in the conversation: are things like nature-based solutions really ‘low tech’? Could these classifications be more harmful than helpful? In all, the future of ‘Smart Cities’ could resemble a post-apocalyptic Ridley Scott film waiting to happen, or it could culminate in a vision where the human and non-human come together to create vibrant, inclusive communities—the decisions we make now will govern the urban trajectory.

- V for Vendetta, directed by James McTeigue (Warner Bros. Pictures, 2006), 00:03:42 .https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NJlgkgiBlTg ↩︎

- “What Is Placemaking?,” Project for Public Spaces, 2007, https://www.pps.org/article/what-is-placemaking. ↩︎

- “About | Responsible Sensing Lab,” Responsible Sensing Lab, n.d., https://responsiblesensinglab.org/about. ↩︎

- Claire Schumann, “Robots for a Cleaner Amsterdam: Roadmapping Waste Relationships for the Next Decade” TU Delft Research Repository, Faculty of Industrial Design Engineering, (June 2023): 86. http://resolver.tudelft.nl/uuid:a530c506-56c1-4888-9596-f93769c0299f. ↩︎

- Schumann, “Robots for a Cleaner Amsterdam,” 88. ↩︎

- Schumann, “Robots for a Cleaner Amsterdam,” 116. ↩︎

- Nanya Sudhir, “How Low-Cost, Low-Tech, High Data Smart Cities Are Paving the Way for the Future,” Container Magazine, August 21, 2023, https://containermagazine.co.uk/how-low-cost-low-tech-high-data-smart-cities-are-paving-the-way-for-the-future/. ↩︎

- “Urban AirQ,” Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Metropolitan Solutions, n.d., https://www.ams-institute.org/urban-challenges/resilient-cities/urban-airq2/.

↩︎ - “What We Do,” Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team (blog), February 6, 2018, https://www.hotosm.org/what-we-do. ↩︎

- Kars Alfrink et al., “Contestable AI by Design: Towards a Framework,” Minds and Machines 33, no. 4 (August 13, 2022): 614, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11023-022-09611-z.

↩︎ - Alfrink et al., “Contestable AI by Design: Towards a Framework,” 615.

↩︎ - Alfrink et al., “Contestable AI by Design: Towards a Framework,” 615.

↩︎

References

“About | Responsible Sensing Lab.” Responsible Sensing Lab. n.d. https://responsiblesensinglab.org/about.

“Urban AirQ.” Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Metropolitan Solutions, n.d. https://www.ams-institute.org/urban-challenges/resilient-cities/urban-airq2/.

“What Is Placemaking?” Project for Public Spaces. 2007. https://www.pps.org/article/what-is-placemaking.

Alfrink, Kars, Ianus Keller, Gerd Kortuem, and Neelke Doorn. “Contestable AI by Design: Towards a Framework.” Minds and Machines 33, no. 4 (August 13, 2022): 613–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11023-022-09611-z.

Alfrink, Kars, Ianus Keller, Neelke Doorn, and Gerd Kortuem. “Contestable Camera Cars: A Speculative Design Exploration of Public AI That Is Open and Responsive to Dispute.” CHI ’23: Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, April 19, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1145/3544548.3580984.

Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team. “What We Do,” February 6, 2018. https://www.hotosm.org/what-we-do.

McTeigue, James, director. V for Vendetta. Warner Bros. Pictures, 2006. 0 hr., 3 min. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NJlgkgiBlTg

Schumann, Claire. “Robots for a Cleaner Amsterdam: Roadmapping Waste Relationships for the Next Decade.” TU Delft Research Repository, Faculty of Industrial Design Engineering, (June 2023): 86. http://resolver.tudelft.nl/uuid:a530c506-56c1-4888-9596-f93769c0299f.

Sudhir, Nanya. “How Low-Cost, Low-Tech, High Data Smart Cities Are Paving the Way for the Future.” Container Magazine, August 21, 2023. https://containermagazine.co.uk/how-low-cost-low-tech-high-data-smart-cities-are-paving-the-way-for-the-future/.