As an urbanist born and raised in Amsterdam, I’m used to comforting international colleagues with the fact that a bike-friendly city wasn’t achieved overnight. For Amsterdam it has been a trajectory of over 40 years of activism, persuasion and policy making that got us to where we are today. But working on public space and placemaking the past decade, it is easy to notice that more cities around Europe are catching up at lightning speed. Amsterdam has dropped to the 4th position on Copenhagenize’ list of most bike-friendly cities in 2025. And for everyone keeping their eye on the urbanism field lately, it’s easy to say that Paris (#5) is one of the current front-runners in Europe, leapfrogging on bike infrastructure, pioneering the 15-minute city approach and radically greening the city, having an incredible impact on cutting greenhouse emissions and improving the city’s air quality. And it is interesting to unpack some of its success factors.

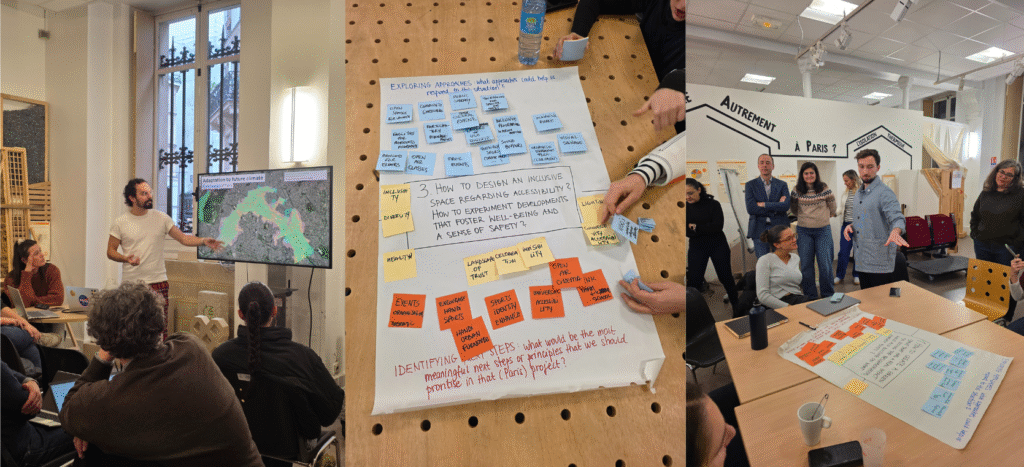

Last week we had the pleasure to be hosted by the City of Paris for the bi-annual project meeting of ReGreeneration, an Horizon Europe project in which 9 cities transform underused spaces in underprivileged neighbourhoods into green and loveable places for people. As Placemaking Europe we are supporting the cities to strengthen their social engagement strategies. Paris’ pilot project within ReGreeneration, the extension of the Suzanne Lenglen Park at the expense of the Heliport, already demonstrates how the city is supporting to rearrange commercial functions in order to create more public spaces for people. But we gained a lot of in-depth insights on many more best practices and strategies of our host city, to combat the climate emergency:

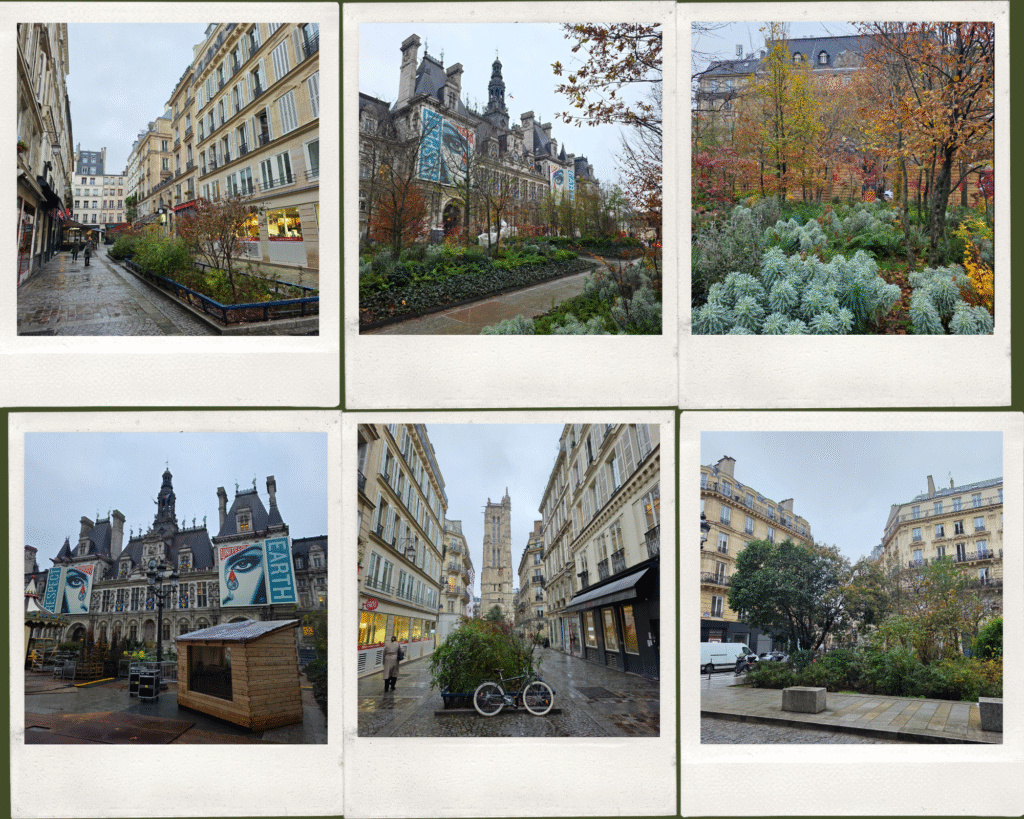

- Over the past years Paris added 1050 kilometers of bike lanes, and now officially has more bikes than cars

- 1600 parking spots are permanently removed, after making the case that 85-90% of the public space was devoted to cars, while only 20% of Parisians own a car. Speaking of spatial injustice.

- Streets that were dominated by cars are transformed into ‘garden streets’, with the ambition to change 40% of the city’s surfaces into green or climate adaptive spaces.

- 131 schoolyards are rewilded into urban oases, and many schools are now sitting within ‘school streets’ where slow traffic is prioritized

- Through educational gardens children and their families are learning to live in closer relationship with nature, getting their hands dirty and engage in risky play

- Cemeteries are now treated as urban biodiversity hotspots; among them the famous Pere Lachaise, where birds and butterflies thrive nowadays

- The city has managed to decrease 40% of the air pollution between 2007 and 2022, with many measures combined. Its mobility interventions being the most impactful.

- The city doubled the amount of landscapers employed, from 40 to 80, acknowledging such expertise is now central to Paris’ urban movement

All this would have never emerged without bold decisions inside the city administration – decisions driven by courage, a pioneering mindset, and a willingness to challenge the status quo.

A couple of things that really stood out to us:

The power of dialogue

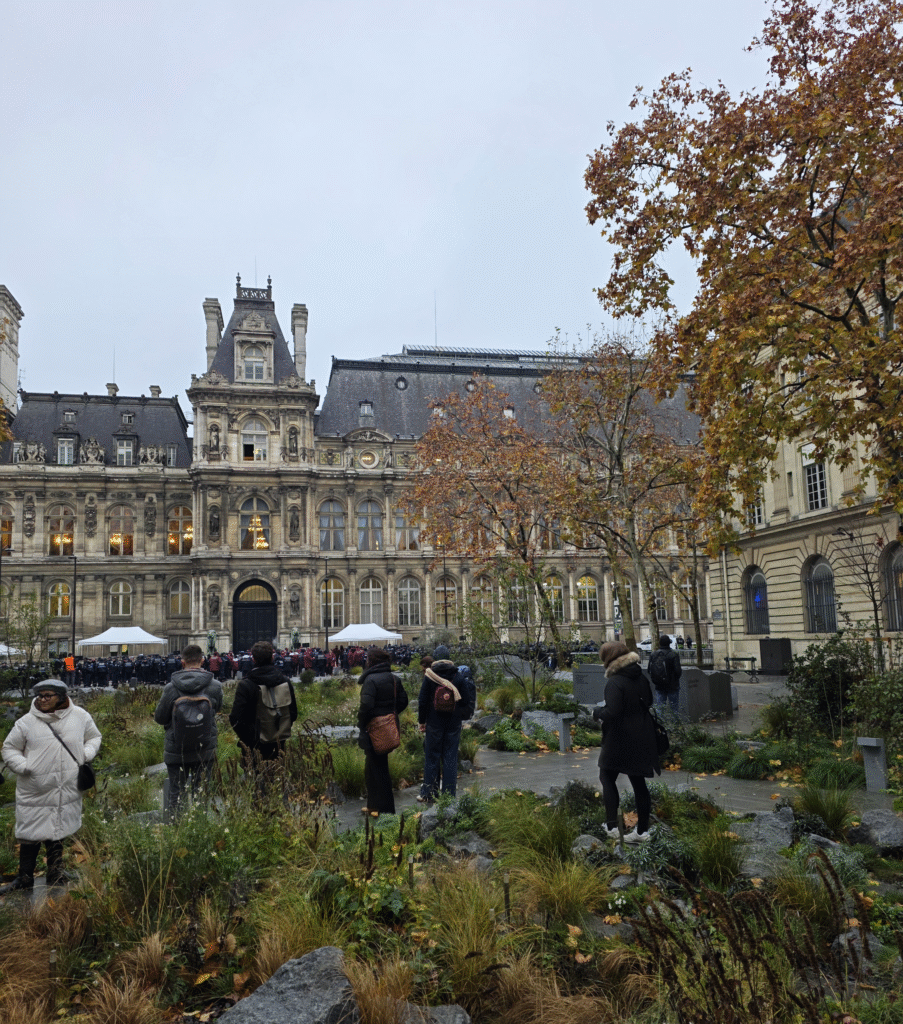

The city administration doesn’t shy away from resolving tough dilemmas between the interests of heritage preservation and adaptive reuse. The transformation of the square in front of Hotel de Ville into an urban micro-forest is a good example. Reaching consensus on such a symbolic location did not happen overnight. But the shared understanding was clear: leaving things unchanged was not an option. The square was a significant heat island, and meaningful mitigation required rethinking long-held assumptions.

Through dialogue, the city shaped a balanced compromise:

- Historic fountains remained in place, but were integrated into new green structures. Replacing water with vegetation, while keeping the option to reverse it for heritage purposes.

- Views toward key heritage buildings are partly softened by the new urban forest, yet the pathways were designed to preserve important sightlines.

- Social and cultural functions were carefully protected. The central area stays open to host gatherings such as the Christmas market, while added seating, shade, and cooler microclimates now enhance the square’s sociability. Early observations already show increased dwell time and more comfortable use of the space.

And the result speaks for itself. It has radically greened the political heart of the city. And the first results prove beneficial for biodiversity, while also providing a great place to linger for Parisians, who avoided the place in summer because of the accumulating heat.

The courage to rethink what Paris is famous for

Paris is one of a kind – and that translates into its typography, materials and shapes. But this also means that solutions cannot be copied-pasted from elsewhere. Instead, the city must identify interventions that address the core of its challenges. That approach is only possible through thorough analysis, supported by continuous data monitoring that allows decisions to be evaluated, adjusted, and refined over time. An example? Paris’ famous zinc roofs prove to be a big factor in its urban heat island effect, and therefore solutions like painting them in lighter colours or greening them are all currently under study. And such adaptive reuse is already tested out at l’Academie du Climat, the former district city hall on Place Baudoyer, that has been transformed into a hub for sustainable associations, events and innovations. And it’s a testing site for the green roof extensions by Roofscapes Studio, which are suitable for heritage buildings. The idea is that these should also lead to lowering the temperatures on the top floors, ensuring that the apartments below remain liveable in the changing climate.

Another urban transformation to highlight is that after the well-known pedestrianization of the banks of the Seine, the city announced in 2024 (just ahead of the Olympics) it has finally achieved its ambitious goal of improving the water quality to such an extent that it’s safe for swimming. And as it was framed by Jenny Andersson (keynote speaker at Placemaking Week Europe 2025 in Reggio Emilia), this is of course an example of a profound systems’ approaches to regeneration, as it involved a lot of upriver changes to end its pollution.

Now how did Paris achieve all this

As I’ve been hearing people say ‘yeah, but we’re not Amsterdam’ for many years, Paris is often facing a similar response in the placemaking field nowadays. ‘Of course Paris could, but we can never achieve that’. Such a response always sparks my curiosity in the secret ingredients behind such an impactful transformation. So throughout the days I asked deputy mayor Lamia El Aaraje, and Céleste Rouberol, Léa Gratas and their colleagues what it takes to make a change.

My key takeaways from these conversations:

- The political will and courage -of mayor Anne Hidalgo and her team in this case- to prioritize the climate emergency over potential financial constraints or conservative pushback

- Tactical experimentation on strategically chosen locations, within the framework of a long-term vision and followed by high-quality implementation of the eventual transformations. This helps build public support, even if there’s a bit of scepticism to begin with. Once people experience the change, they most likely back it up.

- An intentional process wisely balancing the need for strong leadership at times, and participatory actions at others. Not all of the urgent transitions we’re facing today benefit from a co-creative approach, which has the risk of ending up with a compromise, instead of the most impactful solution for the pressing challenge.

- The technical expertise to solve seemingly unsolvable challenges, try novel solutions, monitor their effect and take lessons into account when implementing the next transformation.

The upcoming elections in Paris in 2026 will shape the path forward, but it’s certain to say that some of its experiments will be difficult to change back, because Parisians have embraced them wholeheartedly by now.