What makes a public space inclusive?

Inclusion is a central topic in EU discourse and planning. Public space is one of the main arenas where social cohesion can be fostered in cities. European municipalities however, continue to struggle with designing and supporting socially inclusive public spaces. The Inclusive City consortium 1has been reflecting on what makes a city ‘inclusive’ as a starting point for our Urban Living Labs (ULLs) in Vienna, Oslo, Rotterdam, Budapest, and Rome. In our Inclusive Placemaking Inspirational Cookbook, we defined inclusion as supporting “environments where everyone, regardless of their background or abilities, can participate fully in social, economic, and cultural life (Bösker et al, 2024).” The key features of an inclusive city that we defined in this work were:

- Accessibility: Addressing physical barriers as well as intangible barriers to access such as fear or discomfort for certain groups of people.

- Safety: Physical elements (good lighting and well-maintained facilities) as well as intangible elements that lead to feelings of safety or unsafety for specific groups.

- Diverse Activities: Offering a variety of activities and amenities that cater to different interests, gender, cultures, backgrounds and age groups.

- Community Engagement: Involving local residents in the planning and design process to ensure the space meets their needs and reflects their cultural and social values.

- Intercultural Design: Designing the space to reflect and celebrate the diversity of the community, promoting interaction and understanding among different cultural groups.

- Equity: Providing equitable access to resources and opportunities within the space.

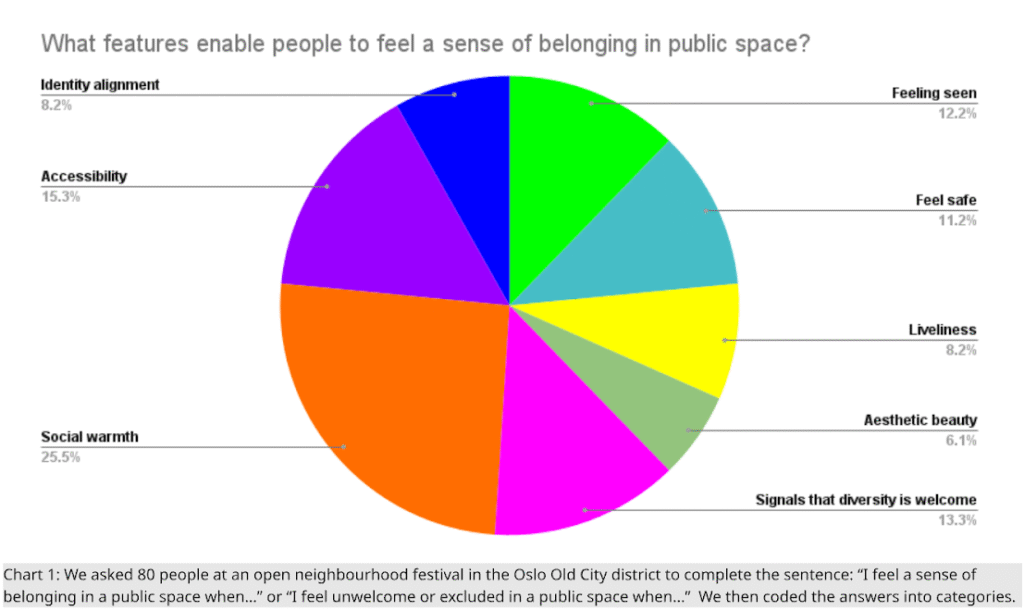

In our Oslo Urban Living Lab work for Inclusive City, we began by reflecting on what inclusion means locally in Oslo—what is needed to make a truly inclusive neighbourhood. We asked local people in the neighbourhood where we were working to help us to better understand what makes public spaces feel more inclusive to them. The answers that came up were similar to what we had reflected on in the Inclusive Placemaking cookbook, but they also deepened our understanding of local people’s inclusivity needs. Some of the responses that came up were:

“I feel a sense of belonging in a public space when I see people smiling or there is a welcoming atmosphere”

“I feel included when I see that a diversity of people are present”

“When I am given attention and not ignored”

“When I feel safe and it feels safe for my kids to play”

“When the space is lively instead of empty”

We coded these answers into eight categories, which reflect what it means to feel included in public space in Oslo: 1. Social warmth; 2. Signals that diversity is welcome; 3. Feeling seen; 4. Accessibility; 5. Feel safe; 6. Liveliness; 7. Identity alignment; and 8. Aesthetic beauty.

These responses led us to reflect on the connection between inclusivity and belonging in public space. With this input, we started planning our public space interventions for the project.

The first activity that we planned dove deeper into the importance of being seen to having a sense of belonging in public space.

How can we support more diverse actors in the neighbourhood to be ‘seen’ by others?

To understand the challenges to local diversity, we began by reflecting on what aspects of life are considered unacceptable to take up space in our city. Based on this, we planned a series of city walks following a Jane’s Walk2 type format, together with local residents, where we reflected together on these ‘unseen’ aspects–we called these the “Unseen City” Walks.

In the Unseen City Walks, our aim was to open up a dialogue with local residents and experts on what is considered unacceptable to take up space in the city. The walks were about making visible what is conventionally ‘unacceptable,’ and opening up a dialogue about what is and is not ‘allowed’ to belong within a 15 minute city. Each walk was led by an expert in one of the unseen city elements. These unseen elements included urban ‘nature’ life (led by the Norwegian Botanical Association), blue collar or production work in the city (led by Fragment), the buried rivers (led by the Oslo River Forum), edible plants in urban space (led by the foraging non-profit Sanke), and people who have suffered from homelessness or substance abuse challenges (led by the forum for a more human drug policy’s company Gatestemmer).

The goal of the walks was to have an open and informal environment where we could engage together with local residents on these issues, while creating an informal and welcoming environment. We did this through the walk format itself, and by formatting the walks in groups of a maximum of 15-20 people per walk. The small group format was chosen to encourage conversations between the topic expert and participants, as well as amongst participants. The walks were organized on a series of Sunday afternoons (usually 1-3pm) over the course of 6 weeks (one walk per week, on a different topic each week).

During the walks we discussed:

- how “messy” plant life is often weeded out in favor of tidiness, order, and decorative control;

- how manual labor, blue collar work, and noisy or “ugly” production are displaced in the 15 minute city by lifestyle economies and real estate value;

- how informal greenspaces are forgotten in municipal plans;

- how nature finds a way to push through and affect the city no matter how deep we try to bury it;

- how there is free food to be found all over the city–but who has the right to take it?;

- how people experiencing difficult life situations are hyper visible on the street but rarely feel ‘seen’ by those passing by.

What does it mean to feel ‘seen’ in public space?

For us, to feel seen means to have opportunities to develop social attachments with others. The Inclusive City Oslo urban living lab (ULL) operates within a theory of change that has the long term objective of supporting more diverse forms of social infrastructure for a just and resilient neighbourhood. The project’s conceptual foundation is grounded in the capabilities approach, particularly focusing on the capability of affiliation.

The capabilities approach, developed by Amartya Sen and further elaborated by Martha Nussbaum and others, is an evaluative and ethical framework used to assess social justice. It asks the fundamental question: What is each person able to do and to be? This approach recognizes that individuals need differing levels of resources if they are to come up to the same level of capability to function (Nussbaum, 2003) and that by understanding capability inequalities, it is possible to provide concrete directions on where to start to make societies more just.

Having the capability of affiliation refers to the ability of individuals to engage in social interactions with others, to be treated with dignity, and to develop a sense of belonging.

Through the lens of the capabilities approach we are better able to understand why feeling “seen” was one of the most common answers to come up in our surveys on inclusivity in public space, and to contemplate what being ‘seen’ means for placemaking practice.

Feeling ‘seen’ in the city means not just to be noticed, but also to be valued positively. It encompasses not just physical but psychological recognition–to be noticed, acknowledged, valued, and validated by others and vice versa. Baumeisler and Leary (1995) relate this to belonging, affiliation, and social recognition. They argue that the need to belong requires long term affiliative connection and stability. In their view, being ‘seen’ is therefore a feeling of being accepted as a part of a group or a place. In placemaking practice, we are able to work with building this sense of belonging through action when participants have valuable roles–analysing a space together, planting a garden, co-creating change, building something in public space, protesting together, or picking fruit and pressing juice together.

On our Unseen City walk together with the guides who had experienced substance abuse challenges and houselessness, our guide June spoke about the social exclusion that she had often felt from passerbys, and alternatively of the supportive community of fellow users. She told the story of how one night when she was sleeping in a park and it was cold outside, a passerby came and placed a warm blanket over her. She talked about how most of the people that she knew living on the street spoke of small moments similar to this, where they experienced being seen and accepted in public space by others.

The capabilities approach offers us a framework to understand why this moment was important to June, and what being ‘seen’ means:

- To feel that you have the opportunity to engage in social interactions with others.

- To have opportunities to be treated with dignity by others and to treat others with dignity.

- To feel that this is a place where opportunities to develop a sense of belonging together with others are available.

Being seen is important because of the opportunities that it opens up for us as individuals in a community. When we are ‘seen,’ we have more opportunities to create social relationships with others which can enable us to feel safe, to have a voice in public decisions, and to access help when needed. We can as practitioners however, fall prey to ‘window dressing’ the challenges. Building the capability for affiliation for more individuals is a long term process, and our small local actions need to be tied to structural changes and embedded in the needs of stable local groups and systems in order to make a difference. Working with the concept of inclusion means working to understand what we and the municipalities that we work in can do to enable individuals from different cultural backgrounds, ages, genders, socio-economic backgrounds, and lived experiences to feel ‘seen’ by others.

So what can you do as a practitioner to enable others to feel ‘seen’ in your city?

The Oslo Inclusive City ULL is managed by Natural State and Fragment Oslo. To learn more about the Inclusive City project or the Oslo Inclusive City ULL, follow us on LinkedIn or contact the Oslo ULL manager.

- Inclusive City is a three year research-oriented project within the Driving Urban Transitions (DUT) partnership, which takes a critical look at the gaps in our placemaking practices and will develop a set of tools, methods, and policies to support the inclusive use of public spaces. The project runs from January 2024 to December 2026.

↩︎ - Jane’s Walks are community led walking tours celebrating the work of Jane Jacobs. The walks are organized as an annual global festival where local people walk together to tell stories about their communities, connect with neighbours, and discover new aspects of their neighbourhoods. ↩︎